"Writing can save us, but we can also save our writing through caring for ourselves."

writer, editor, & educator Han VanderHart on the "illicit" pleasure of writing in the margins of a full life, how the world opens up with deep attention, and the necessity of self-permission

This is a Beginner’s Mind interview, a series that explores the intersection of mindfulness and creative practice. Zen master Shunryū Suzuki Roshi said, “In the beginner’s mind, there are many possibilities; in the expert’s mind, there are few.” This series shines a light on the practices that sustain people in their daily lives and open the path to new possibilities. If you know (or are) a writer, creative person, teacher, or practitioner with practices you’d like to share, just reply to this newsletter to be in touch with me.

Han VanderHart is a poet, editor, educator, and arts organizer I’ve admired from afar for many years. I first came to know Han through their generous efforts to amplify the work of others and build community online. Then, a friend recommended Han’s first book, What Pecan Light, and I was transfixed by it. Han’s poems explore subjects it would be easier to skate over the surface of: family trauma, racism, and the silences we keep. When Han visited my Madwomen workshop this past fall, they listened very closely when they were asked questions by the writers in the room. With each question, Han would pause to think for a minute before answering. I noticed it because it felt awkward to me at times, but I also marveled at it. It stayed with me, that pause.

I’ve been eagerly awaiting Han’s second poetry collection, Larks, forthcoming this March from Ohio University Press. Diane Seuss says of Larks, “Han VanderHart has demonstrated that survival is a profound act of the imagination.” Every time I read a Han VanderHart poem, I marvel at the way Han implicates the speaker and bends the lyric to their purposes—the way they speak of what is difficult, of what is unspeakable—how they name anger, violence, erasure—and move toward tenderness.

Read on to hear from Han, on the "illicit" pleasure of writing in the margins of a full life, how the world opens up with deep attention, and the necessity of looking again. Plus, Han shares a bevy of incredible reading recs and a powerful writing & drawing prompt called “The House of Memory.” ✨✨

What is your writing practice like? Do you have any writing rituals that help you?

Like many caretakers, teachers, and wage-earners, my writing practice takes place in the margins (I like this analogy, since texts have margins, too, and readers engage them there, writing their own notes as marginalia), fitting in the odd hours. In fact, I often think of Eugenio Montale’s essay “The Second Profession,” which I recently went back and reread, only to realize I’ve misremembered it for years—it’s not about poetry as the second profession to your “real,” daytime job, but your paying, daytime job as the second profession to your poetry. I can’t recommend Montale enough right now—his anti-fascist literature and poetry essays or his stunning poetry; he was writing his poem “The Lemon Trees” in Italy in 1922 when Mussolini marched on Rome with 30,000 fascists. But I digress (do I? This is America).

My writing ritual is change—bless Octavia E. Butler—and currently includes a precious hour on M/W/F mornings before work, on the couch with my anxious pitbull Bug, after my children have gone to school. Bug sleeps with his head buried in my side, and I write a poem longhand or read, and have that quiet, reflective time with him. It is so calm and grounding. Interjection: I have to laugh, because since that time, I have entered the winter break, and my stolen writing time has shifted, evaporated, run away on little cat feet. “Blessed are the flexible, for they will not be bent out of shape,” indeed (Oklahoma). I will never be a 5am writing club member. I will never have a regular schedule. I will never be Ursula LeGuin. I mean, maybe. Maybe someday. But right now my life is precarity, is three different school schedules and many small human and non-human animals, and a delicate physical and mental health balance.

I take my writing time in snatches and stolen moments, and relish it when I can; it feels a bit like theft, like illicitness. I kind of like it this way, and always have. I love stolen time. My favorite proverb is “food eaten in secret is delicious.”

What are your mindfulness practices? Can you describe them and what they bring into your life?

It very much depends—I don’t do anything religiously. I meditate, I practice yoga. I read. I sit outside and stare up at the trees. I feel like my life is stitched intermittently with mindfulness. My therapist, maybe a year ago, asked me to consider what is not mindfulness, or where mindfulness actually ends and begins, and certainly bringing mindfulness into my ordinary life, and making my life one of deep attention, is a goal of mine. For example, actually speaking and listening with a child or another person (which, yes, I failed at just last night, glancing away from my child to my phone when they were trying to tell me something involved). It is a practice I fail at and return to, because I do love paying deep attention to another person—I feel like people open up this way; the whole world does, really.

I did notice that when I had taken a long break from writing poetry (2011-2016, when I had my children), and I came back to writing poetry, an attention sensor immediately lit up in my brain, and I began noticing so much more about the world, in order to write about it. It was like my noticing became 4D, supersaturated, reawakened. Verlyn Klinkenborg (in Several Short Sentences on Writing, I can never recommend this book enough) notes that writers notice what they notice, and amen, amen.

What is an important mantra or motto for you related to your writing/creative/mindfulness practices? What piece of wisdom do you have on a post-it note to help you remember it?

Probably Iris Murdoch’s “let me look again,” which is so simple that I don’t need it on a note, and comes from her story about M (Mother-in-law) and D (daughter-in-law), in her essay “The Idea of Perfection.” It admits that we get things wrong, as humans, and that we must turn our attention back towards another person, with generosity, with love, with humility.

And we can’t just order ourselves to do this at any time—we need cooling time, to cite the title of another incredible writer, C.D. Wright (from the book’s description: “C.D. Wright takes her title [Cooling Time] from a line of legal defense, peculiar to Texas courts, in which it is held that if a man kills before having had time ‘to cool’ after receiving an injury or an insult he is not guilty of murder). But after the cooling, and giving ourselves the space we need to recover and rest and process, we can look again, whether that’s to a manuscript that covers difficult content, or to a tender piece of writing that has received multiple rejections, or to a friendship that needs repair. “Art is not apart, but a part of,” to quote Wright once more.

And to quote Murdoch again: “the real…is the proper object of love.” That is: we see best through love, we read best through love—texts as well as each other.

Are there any books / writers / teachers that have been transformative for you that you would recommend to readers?

Oh, lordy—bell hooks, currently. I think as writers, self-permission is the most essential aspect of our writing, as self-permission is an integral part of showing up for ourselves. I was taught, as an Evangelical child, to count down the fingers of one hand as though God was talking to me, saying, “I – will – never – leave – you.” And, genuinely, this was a helpful thing to teach a child who felt isolated and abandoned. But bell hooks, in her book Communion, reminds her reader that the person who will never abandon you is yourself. Practicing showing up for yourself as a writer is cultivating the most important relationship in your life, particularly if you have caregiving roles (which are very hard to escape in a lifetime, one way or another!), or health challenges: the one with yourself. No one else can ultimately affirm you as a writer, or tell you when you need to rest, or know what you need, the way you can for yourself. The self also has limits, and there is a kind of self-knowing we can only have access to through community with others—and this, for me, is where reading Aristotle (I highly recommend the Nichomachean Ethics) and Iris Murdoch (her novel The Bell, her three essays collected in The Sovereignty of Good) come into play. I don’t think language and ethics exist apart from each other.

How have writing and/or mindfulness practices helped you in your life?

I know daily journaling saved my life as a child, comforted me, gave me companionship, and meditation carried me through trauma therapy as an adult. I began writing poetry again in 2016, because as a survivor, I was frankly not surviving the 2016 election, and writing saved me then, too. There is a reason therapists assign journaling and creative expression—I think of Anne Sexton, and how important writing poetry was to her mental health and survival, and how devastating it was when she felt the poems were failing her. I want to be honest and state that I also had maladaptive coping mechanisms (alcohol), and thank God I survived them and found good mental healthcare and antidepressants (neither of which Sexton, I will swiftly point out, had consistently, while also dealing with chronic pain, having her sexuality stigmatized as pathology, and a care provider who abused his power). I think of the British poet Geoffrey Hill, who was very open about how Lithium saved his life and writing, and how his writing came flooding back to him when he began treatment. Writing can save us, but we can also save our writing through caring for ourselves.

A Prompt from Han 📝

I love the simple prompt (learned from Robyn Schiff) which I think of as “House of Memory,” which is to take colored pencils and draw the floorplan of the earliest house of your memory. It is a meditative exercise that breaks me out of my patterned thinking, takes me away from wherever I am in my current thought life.

My students always discover surprising things about themselves when we do this: one remembers a wooden dresser in their childhood bedroom with a pattern of owls in the woodgrain. Another remembers a cabinet in the kitchen they used to hide in; another remembers the curtains in their sister’s room that they lit on fire.

Every time I assign this exercise, I do it alongside the workshop, and a poem arrives out of it. Houses are deep in our psyches (Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space is another recommendation), and tap into our Ur-selves. You can place objects in the rooms, or think about the inhabitants, or the doorways, or the curtains. House of memory is an endlessly generative meditative and creative exercise, in my experience.

Han VanderHart is a queer writer living in Durham, North Carolina. Their second poetry collection Larks, winner of the 2024 Hollis Summers Poetry Prize, is forthcoming in April 2025 from Ohio University Press. Han is also the author of What Pecan Light (Bull City Press, 2021) and has work published in Kenyon Review, The American Poetry Review, The Rumpus, AGNI, and elsewhere. Han hosts Of Poetry Podcast and alongside Amorak Huey co-edits the poetry press, River River Books.

You can find more about Han’s work at their website, subscribe to Han’s substack newsletter, Poetry Notes From Han, and follow them on Instagram @han.vanderhart.

A few poems by Han

“Tornado Warning of my Heart on a Clear Day,” at Psaltery & Lyre

“I Like to Think Emily Dickinson Would Read The Ethical Slut under an Umbrella by the Pool” at DUSIE

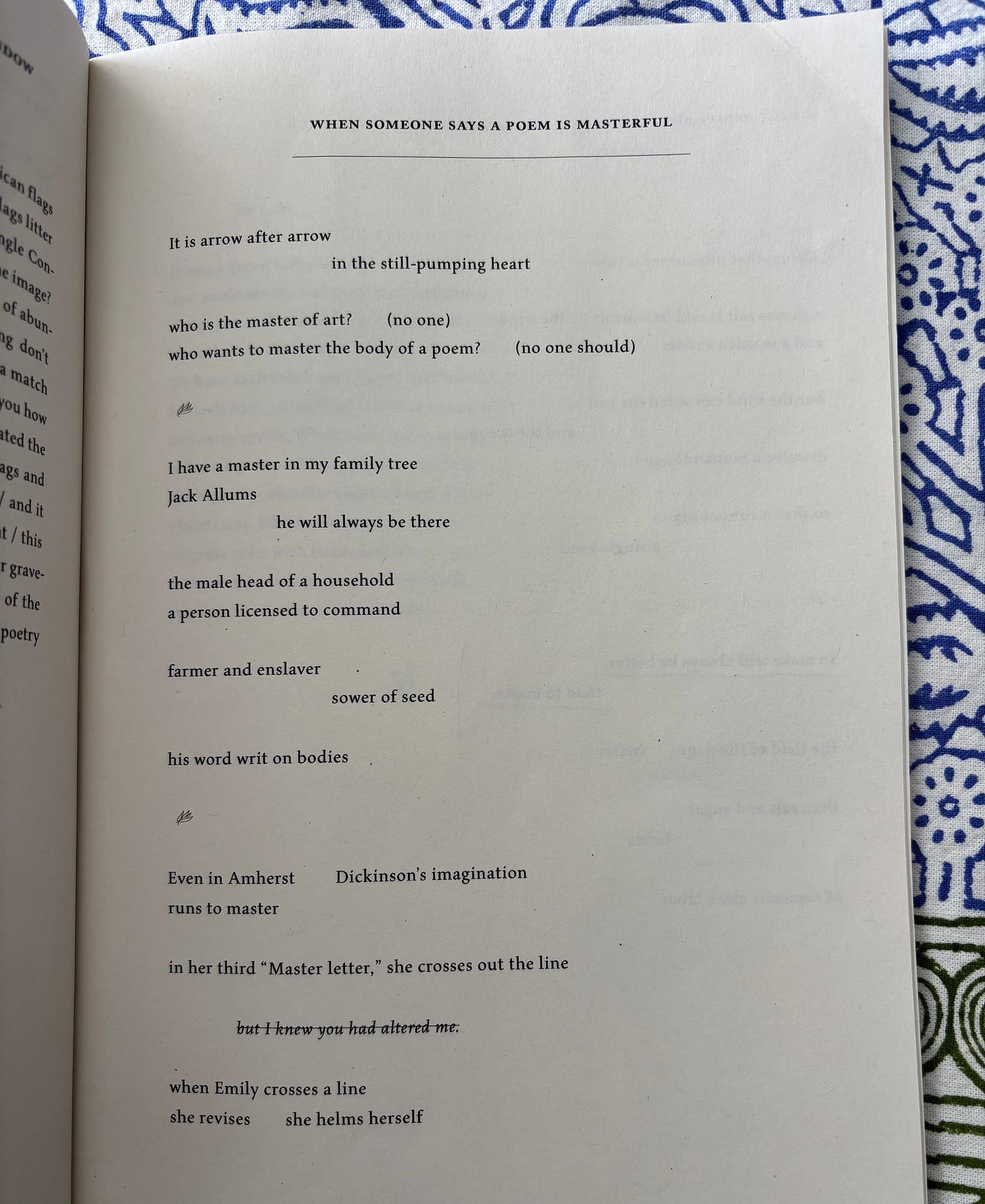

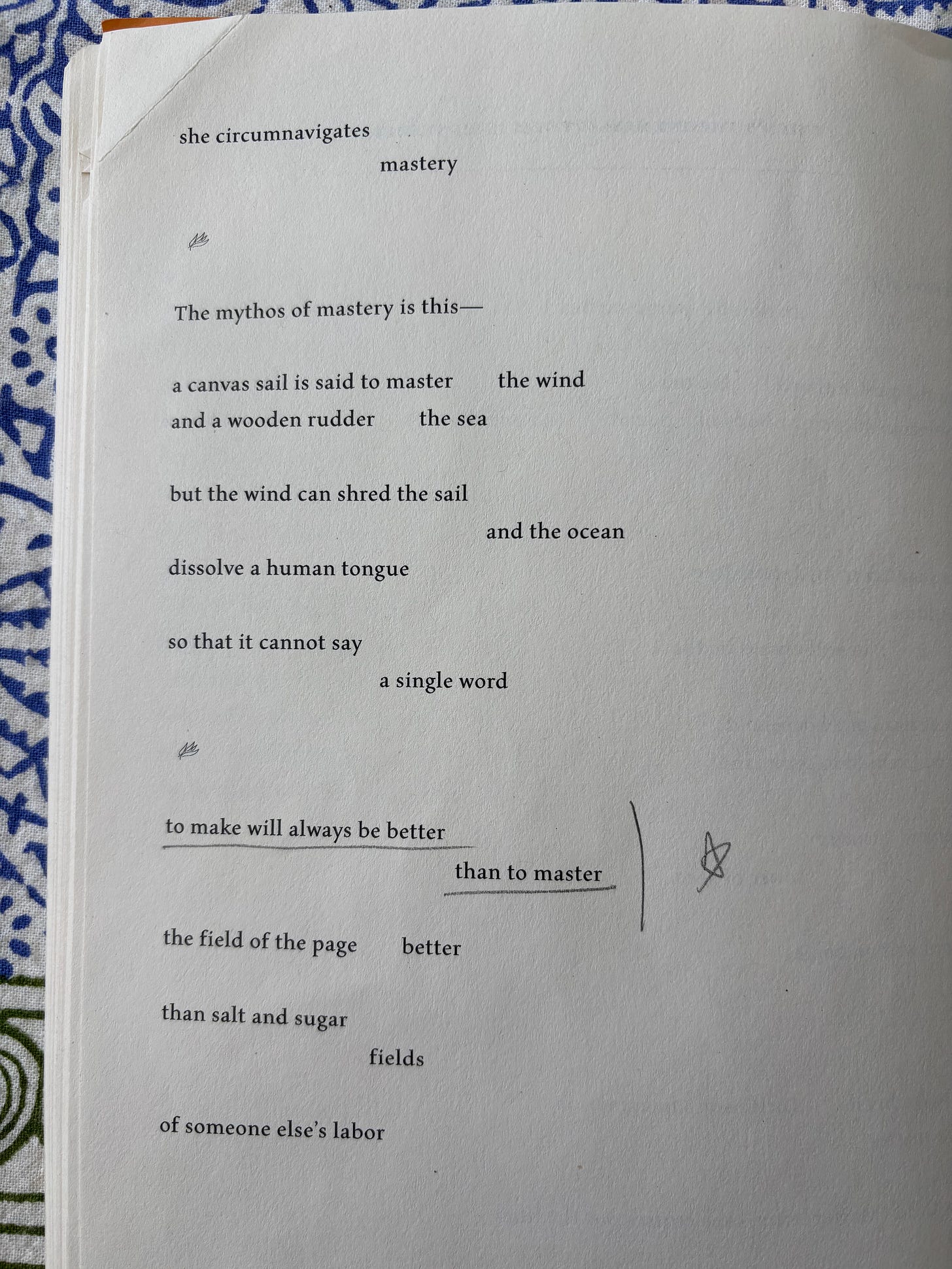

And, below, one of my favorite poems from What Pecan Light, “When Someone Says a Poem is Masterful”

Clicking the heart to like this post, adding a comment, or sending it to a friend is a great, free way to help Han’s work and wisdom find readers. 🩵

Be Where You Are is a newsletter about how to use writing and mindfulness to live more fully where you are. If you value this work, please text it to a friend, or consider a paid subscription (a few dollars a month) to help me keep it going.💥 You can also find me on Instagram or Facebook or find more info at my website. Thank you for reading! 🩵