"Some available strangeness"

poet & editor Carolyn Oliver on writing by hand, the zen of gardening & yardwork, and advice for restarting your creative practice

This is a Beginner’s Mind interview, a series that explores the intersection of mindfulness and creative practice. Zen master Shunryū Suzuki Roshi said, “In the beginner’s mind, there are many possibilities; in the expert’s mind, there are few.” This series shines a light on the practices that sustain people in their daily lives and open the path to new possibilities. If you know (or are) a writer, creative person, teacher, or practitioner with practices you’d like to share, just reply to this newsletter to be in touch with me. Subscribe below to make sure you don’t miss any future interviews.✨✨

I’ve known Carolyn Oliver since we were in grad school seventeen years ago. Back then, I was struck by the incisive questions she asked in our seminar discussions, and how she shared such nuanced understandings with a playful air (no dour, angry grad school poses from Carolyn, no sir, thank god). I didn’t realize she was a formidable poet until many years later when she landed in my Madwomen workshop, deep in the pandemic. Week after week, Carolyn showed up with drafts in a wild range of styles. After waiting until the very end of each workshop to share her poem, she’d have some wickedly brilliant, vulnerable comment about the poem or the process that would make everyone smile and feel seen.

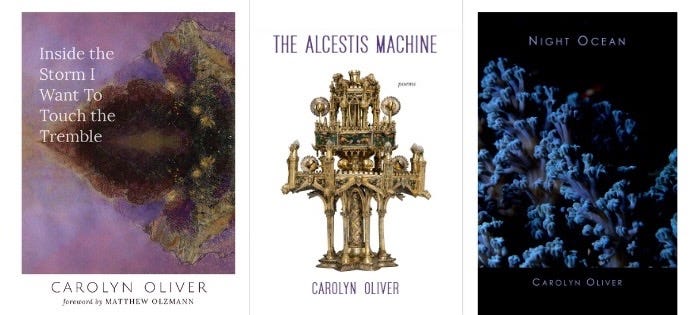

Matthew Olzmann says of Carolyn’s first book, Inside the Storm I Touch the Tremble, that “there’s a distinct sense of an agile mind trying…to take it all in, the whole scale of being alive, every piece, so that she might shape those pieces into something meaningful for us.” Rachel Mennies says of her second book, The Alcestis Machine, just out this fall from Acre Books, “Oliver’s acts of witness tenderly move us from the cosmos to deep inside the body.” Every time I read a Carolyn Oliver piece, I marvel at the alchemy she works on the page. She has a way of playing with language and ideas that makes reality feel more malleable, more full of possibility.

Read on to hear from Carolyn, including the power of writing by longhand, the zen of gardening and yardwork, and wise advice for restarting your writing practice when you get stuck. You’ll also find a prompt from Carolyn and a few of her spellbinding poems. 🪻🪻

What is your writing practice like? Do you have any writing rituals that help you?

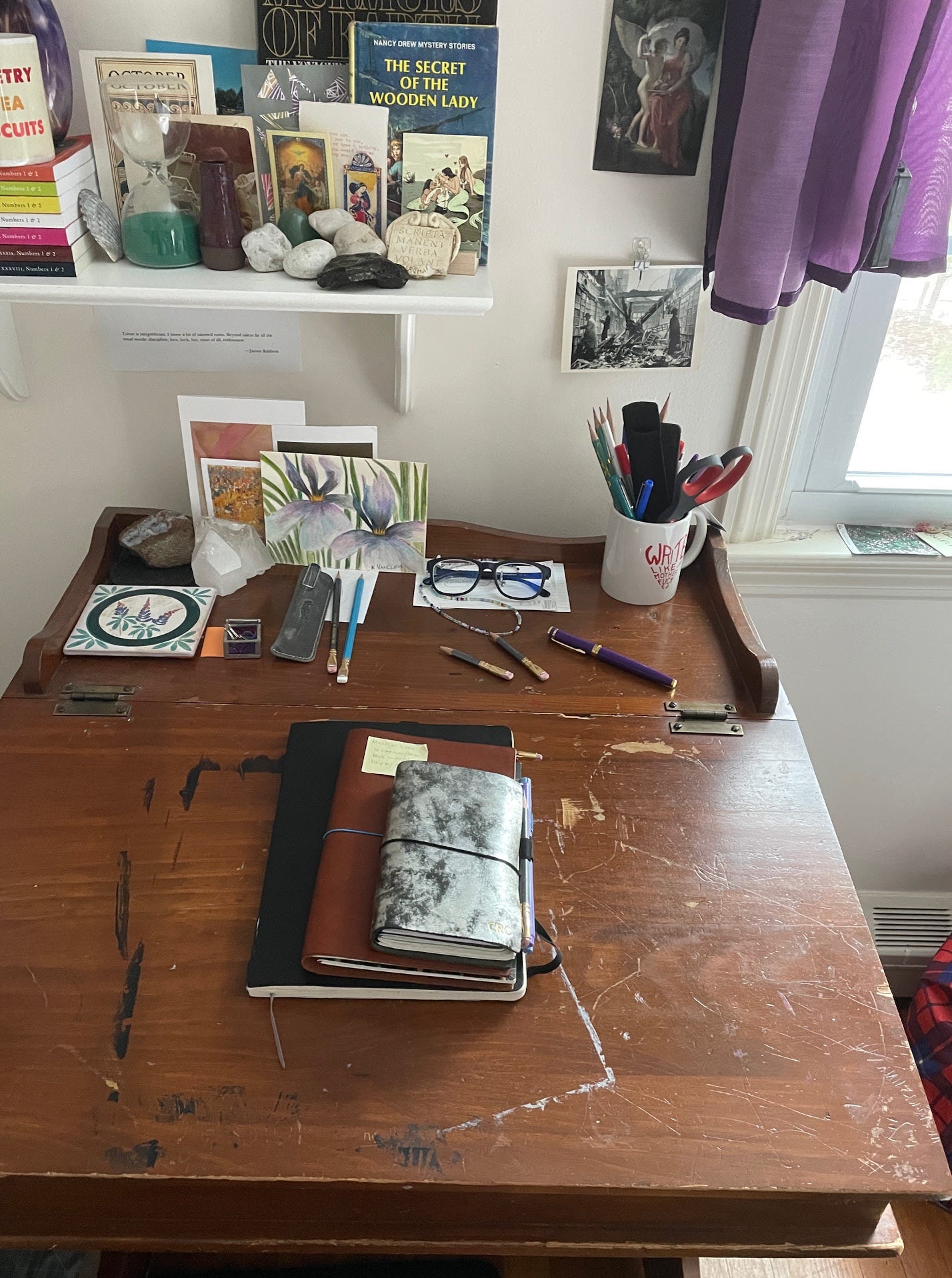

I’ve tried various rituals, but nothing’s stuck, so far. A practice that’s helped me, I think, is to start the workday at my secondhand, rock-strewn, gloriously functional desk, which is reserved for longhand writing, paging through notebooks, and quick reading breaks (and Zoom calls/readings). Most of the poems in The Alcestis Machine were drafted here.

I write in the mornings, and switch to non-writing work in the afternoons—meetings, editing for clients, sending submissions, dealing with what I call administrivia—until my son gets home from school.

When I’m working on poems (prose requires, for me, a different process) I write drafts by hand, in pencil (Blackwing, they really are the best) on yellow legal pads. A poem might go through four to ten or twelve handwritten iterations. Eventually, I type up the revised draft, almost always confident that the poem is a nudge or two from done, almost always in for another fifteen or twenty iterations before I’m ready to send it out. It's rare for a poem to take shape in fewer than, say, a dozen versions.

What are your mindfulness practices? Can you describe them and what they bring into your life?

Because of my neurological framework’s idiosyncrasies, I approach mindfulness in a largely unstructured way.

For example, I’ve been working on noticing—without judgment (so tough!)—my impulse to seek distraction instead of wrestling with or completing the (required, boring, difficult, and/or fiddly) task in front of me. If I notice that impulse, I name it, then ask myself if I can stand to work on the task for five more minutes. Usually, yes; sometimes, I realize I’d been ignoring some simultaneous physical discomfort, which I should address first.

While writing longhand—notes, postcards, drafts—and cooking are ways I unintentionally put myself in a mindful state, I think I’m most present—without conscious effort—when I’m gardening, or doing yardwork. Weeding, watering, sowing, pruning: all require physical effort and attentiveness, but a different sort of attentiveness than what’s required for writing or conversing or conceptual thinking. While I’m debating whether or not I should transplant the snapdragons, my conscious mind doesn’t have the capacity to perform multiple-track rumination.

As I type this, I’m realizing that the carrots I meant to pull last week have no doubt frozen and unfrozen into mush in the interim. I want to note that I’m not *good* at gardening— and I mean that not to denigrate myself, but rather to indicate that I have no intuitive sense of the workings of plants, I tend to fall back on benign neglect as a strategy, and my acquisition of gardening-related skills and knowledge started late and proceeds slowly. I learn one or two new techniques or strategies every season, and that’s fine.

The results of the effort—whether a summer of riotous milkweed and phlox leaning into the walkway, or a volunteer marigold, whether a month of homegrown-tomato sandwiches or one dinner’s worth of potatoes—those results are joyful. But thanks to weather and bugs and rogue chipmunks, a season in the garden never goes exactly to plan; a flower that grew splendidly one year may not even sprout the next (looking at you, delphiniums). I might put in hours and hours sowing fall-harvest vegetables, only to face three months of drought nobody saw coming. Yet it was the process that mattered—that mindful time in the garden. (Though, naturally, these setbacks lead me to reflect on and respect anew the labor and risks involved in farming.)

I meant to tie this up with a writing analogy, but I’ve gone on long enough, and I’m sure you get the idea.

[By the way, if you are a kindly gardener reading this and you grow radishes and beets bigger than lentils, please tell me your secrets. I’m in zone 6B.]

What is an important mantra or motto for you related to your writing & mindfulness practices? What piece of wisdom do you have on a post it note to help you remember it?

Taped up on facing walls in my office:

James Baldwin:

“Talent is insignificant. I know a lot of talented ruins. Beyond talent lie all the usual words: discipline, love, luck, but most of all, endurance.”

W. S. Merwin’s poem “Berryman,” —the printout is dated 2017—which, sometimes, I need to read in its entirety. Here are the last two stanzas:

I had hardly begun to read I asked how can you ever be sure that what you write is really any good at all and he said you can’t you can’t you can never be sure you die without knowing whether anything you wrote was any good if you have to be sure don’t write

What helps you when you get stuck with your writing or mindfulness practices?

In general: Reading, as widely as my shelves and library card permit.

If it’s early on, or if I’m boring myself: I’ll page through my notebooks to see if there’s some available strangeness that would set the poem off-kilter in an interesting way.

When a draft is well underway but jaw-clenchingly uncooperative: If possible, I go outside. Sometimes this means sitting on the front step, watching the bees at work in the asters, or the brazen chipmunks racing through the phlox I should have cut back, or the cars that take the downsloping road too fast. Sometimes I wander around the yard, looking at the raised beds and making plans I’ll forget because I didn’t bring my notebook with me. Sometimes I walk around the block. If the weather’s terrible I pace in the hallway.

What advice would you give someone who is trying to start or restart a writing or mindfulness practice?

This is ultra-specific but: ignore the first page of your notebook, or your legal pad. That first page can seem too charged with significance or overwhelming possibilities. Flip to page two, or better yet, a random page. Draw something unrecognizably weird or abstract in the corner. Now your hand is moving, and no one’s watching, and this page is tucked away . . . it’s safe to write.

A prompt from Carolyn

Bring to mind a friend you miss, a friend who’d welcome a note from you.

With paper/notebook/junk-mail envelope and pen/pencil/marker in hand, take a stroll around the block, or, if that’s not possible, take a tour through a cookbook, or a coffee-table kind of art book you haven’t flipped through in a while.

On your walk, or as you page through the book, be alert to anything that draws your notice—a lost mitten? A pleasingly sharp citrus dressing? An insect painted on a flower petal?

Scribble down a list of your noticings as you go along.

After your stroll, or book tour, re-read your list. Who, or what place, or what experience, pops into your mind?

On a postcard, tell your friend about that place/person/experience.

Mail the postcard.

Carolyn Oliver is the author of The Alcestis Machine (Acre, 2024); Inside the Storm I Want to Touch the Tremble (University of Utah Press, 2022), selected by Matthew Olzmann for the Agha Shahid Ali Prize in Poetry; and three chapbooks, including, most recently, Night Ocean (Seven Kitchens Press, 2023), which was selected for the Rane Arroyo Series. Her poems appear or are forthcoming in Poetry Daily, TriQuarterly, Copper Nickel, Image, Consequence, and elsewhere. Her work has been supported by the Massachusetts Cultural Council and by Mount Auburn Cemetery’s artist-in-residence program. Her honors include the Goldstein Prize from Michigan Quarterly Review, the NEPC’s E. E. Cummings Prize, and the Frank O’Hara Prize from The Worcester Review. Born in Buffalo and raised in Ohio, she now lives with her family in Massachusetts.

For more from Carolyn and her new book The Alcestis Machine

You can find Carolyn’s website here and follow her on IG @carolynroliver

Order her recent book The Alcestis Machine at Bookshop.org and her debut collection Inside the Storm I Want to Touch the Tremble at Amazon (backordered elsewhere)

Listen to Carolyn read “Blueshift” on Youtube HERE

Read Carolyn’s fantastic interview with Millie Tullis about her new book at Psaltery and Lyre

Listen to Carolyn in conversation with Han VanderHart on the Of Poetry Podcast

On Jan 28th, Carolyn is in a (virtual) conversation with Hannah Larrabee for the Notebooks Collective (which looks very cool). Info to register HERE.

Clicking the heart to like this post or adding a comment is a great, free way to help Carolyn’s work and wisdom find readers.

Be Where You Are is a newsletter about how to use writing and mindfulness to live more fully where you are. If you value this work, please text it to a friend, or consider a paid subscription (a few dollars a month) to help me keep it going. 🩵 You can also find me on Instagram or Facebook or find more info at my website. Thank you for reading!⚡⚡

“I know a lot of talented ruins.” Goddamn, James Baldwin. Again why he was America’s greatest essayist. Thanks you for sharing , Carolyn and Emily

Thank you so much, Emily, wise and and generous poet-friend!