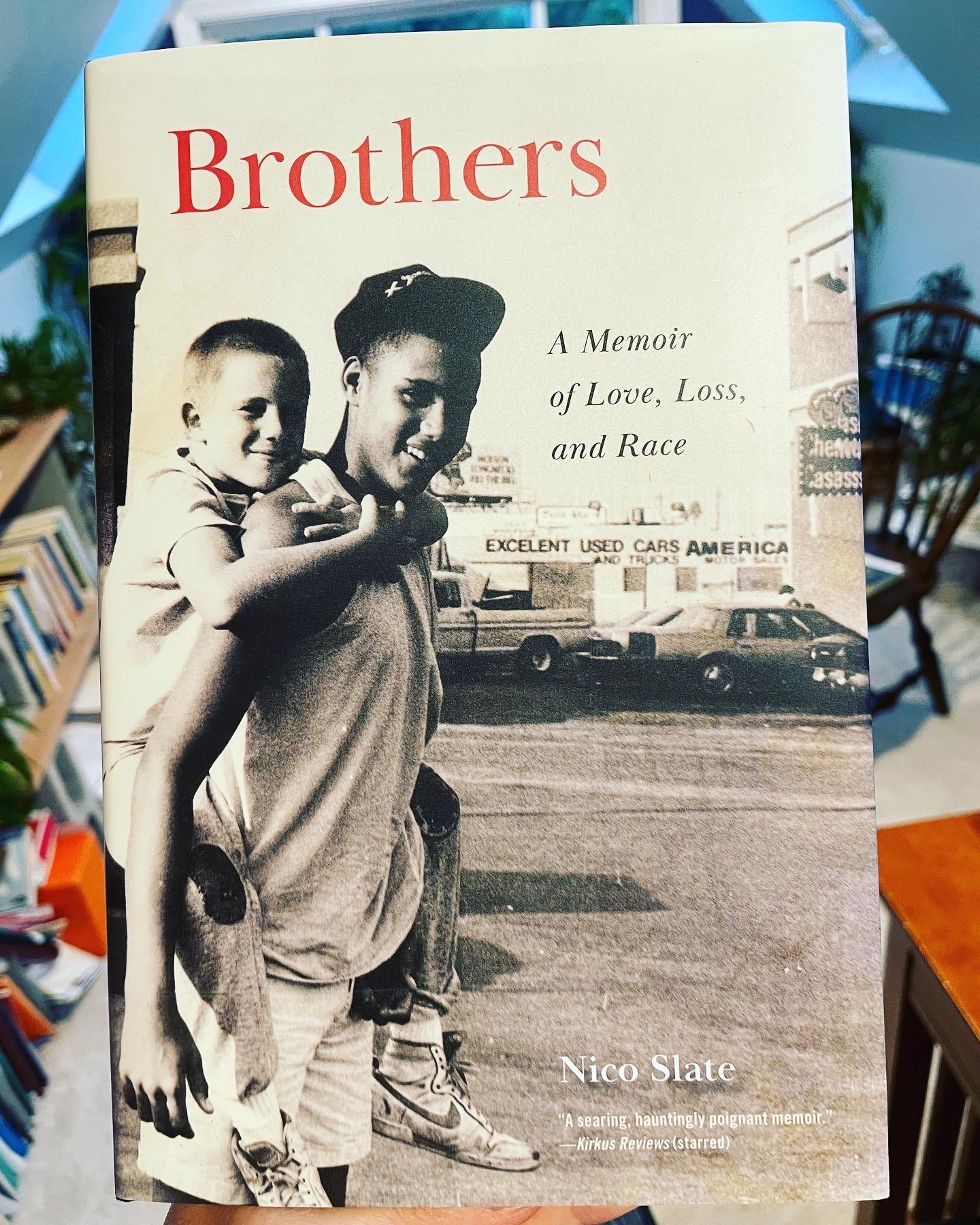

Yesterday, my husband, Nico, had his first book event for his memoir, Brothers: A Memoir of Love, Loss, and Race, which came out a few months ago. The book is about his beloved, late brother, Peter Slate, a rapper, screenwriter and truly remarkable human being. It’s a beautiful book; vivid, deeply researched, and richly imagined and felt.

I witnessed Nico’s process with this book over the past nine years, listening to stories, reading drafts, asking questions, and serving as sounding board and editor. We do this for each other all the time, for whatever project or piece we’re working on, large and small. But even though I’d lived with him through this process and waited years for this book, excited to share it with others, the book event yesterday bowled me over in many ways.

Nico and I never go to each other’s readings because it’s easier to pass the kids back and forth than find a babysitter, but this event was different, so I asked my dad to watch them so I could go on my own. I rushed there sweaty and fried from a day of teaching and meetings, struggled to find parking, then made it just in time to be ushered into a spare auditorium classroom for the event.

Nico doesn’t show up often in my writing. In fact, all week I was planning to write about something else for this post. But now I feel full of revelation, not only about Nico’s book, but also about seeing him—really seeing him—in a new way.

When you’re parenting young children together—or simply living through the crush of life as it is in 2023—whomever you share your life with invariably becomes your copilot, co-worker, co-event planner, and sometimes they become almost like (pardon the comparison) furniture.

When you first fall in love with someone, you study their every little gesture closely, try to name their exact eye color, the way the cowlick at the back of their head stands up in that same funny shape. Then over time, through the power of repetition, what was once a nuanced mystery becomes habitual, familiar. You don’t need to look closely because you’ve already explored that terrain. Your partner becomes—no matter how hard you try—an object that you notice just enough to steer around to get where you’re going, for instance when they’re standing in front of the silverware drawer when you need a fork, as Nico always seems to be.

Many days I have to remind myself to stop and actually look at him when I ask how his day was, because I’m deeply exhausted or there are just so many things to do other than sit and listen. Most of our conversations are about our calendars: “Should I say yes to this or no?” “Do you think three outings is too much in one weekend day?” (yes, omg, YES).

It’s frankly a miracle for anyone to stay loving and actually in love with each other through the ups and downs of life (for instance, going to work with your sweater on inside out—which is something I did just yesterday. Thank god for the student who told me during first period, thus sparing me the shame of walking around like that all day). It’s incredibly difficult to stop and look at each other on an average day, and nearly impossible to really see each other at all. (Did you see this article about looking into each other’s eyes in the NYT?) Sometimes, we’ll go hours without actually looking at each other even though we’re shepherding the kids together or cheering for them at the same soccer game. Time to look at each other is reserved for after 9 pm when the kids finally relent and go to sleep, and by then, our eyes are glazed over by fatigue. I often say I love you to Nico while I’m not even looking at him, when I’m leaving the house in the morning, herding the kids into the car and he’s standing at the front door reminding me to charge the car when I get to work.

But yesterday, I sat and listened to people who know and love Nico in his work life talk about him and his work. I heard him read from his book about his beloved big brother, Peter. I listened to him talk about his process with this book and answer complicated questions with candor and heart. I witnessed him tear up reading a story about Peter comforting him one night when he was terrified to sleep (a story that brings me to tears, too, no matter how many times I read it). I saw and heard this whole other side of him—this vital side that exists when he is out of my presence and that I usually only see in fragments of him talking to people on zoom while I’m trying to keep the kids from interrupting. I saw him as Nico—a historian, a writer, a professor, a colleague, a friend. A little brother still grieving his big brother who was also the closest thing he had to a father.

Even though he’s a natural public speaker, Nico doesn’t like being the center of attention. He shines brightest when he’s listening to his Highlander Folk School tapes for his current project and writing on the porch, wearing fingerless gloves and a hat and scarf (because he’d always rather be outside, even when it’s cold). He shines brightest telling me things I never knew about his heroes, of whom there are many—Pauli Murray or Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay or Anne Braden or Bob Moses. He shines brightest making up a ridiculous game for the kids when they’re bored.

This morning, I woke up thinking about this Rilke quotation (even though Rilke’s wisdom is shadowed for me by his limitations as a human being):

“A merging of two people is an impossibility, and where it seems to exist, it is a hemming-in, a mutual consent that robs one party or both parties of their fullest freedom and development. But once the realization is accepted that even between the closest people infinite distances exist, a marvelous living side-by-side can grow up for them, if they succeed in loving the expanse between them, which gives them the possibility of always seeing each other as a whole and before an immense sky.”

As Nico talked about Peter and answered questions about writing his book, I saw him across “the expanse between” us, I saw him “as a whole and before an immense sky.”

Perhaps I was primed for this kind of seeing by Nico’s book, which tries to see Peter’s complexities and to tell who he was as truly as he can. And by what Robin D.G. Kelley sees in this book—that Peter “managed to make those he loved whole.” I saw Nico—and this difficult work he had done—from an angle normally obscured to me and he was—and is—beautiful.

This morning, I’m trying to hang onto that moment, but it’s already starting to recede back into the familiar. Conversations about this week and who will do cross-country and piano lesson drop-off and pick-ups and what time we need to leave the house today.

I’m hanging onto what I saw and felt when the veil of familiarity lifted for that moment and I could see the person I love as a whole. The person who I know tries to see me, too. I know I will fail again and again, but I can still vaguely touch what that kind of seeing feels like. I can keep trying.

Be Where You Are is a newsletter about how to use writing and mindfulness to be where you are. You’re always welcome to reply to this email, comment below, or find me on instagram (@mohnslate) or elsewhere. If you enjoyed this, I’d love it if you would subscribe, share this post, or send it to a friend.

You're most welcome, Emily.

This is a lovely tribute to Nico, but also a fine description of the complexity, difficulty and indescribable pleasure of being in love with and kind to that other self that a partner is.